JOAN FONTCUBERTA:

Is There Anything like Photography in Googlegrames?

JOAN FONTCUBERTA:

Is There Anything like Photography in Googlegrames?

pol capdevila

Introduction

We are now coming into a new era for photography. This common place in many theoreticians does not mean that we are already able to figure out the transcendental changes that are taking place in the world of images and, consequently, in our worldview. This places us in the challenging and privileged situation of stating the hermeneutical questions that will prepare us to understand such changes. This paper is trying to bring a modest contribution by formulating some of the problems I think have a primordial interest to start coping with these shifts. I am doing it by reflecting on the paradoxical nature of Joan Fontcuberta’s Googlegrames. Since Googlegrames can be understood a sort of images that bring to the last consequences some of the features of digital images, I will take them as a paradigmatic symptom of the problems that a theory of picture has to deal with in this age of uncertainty. I will divide my analysis of Fontcuberta’s Googlegrames in three conventional sections: the first one referred to the nature of the image (this will show some ontological questions); the second one referred to the artist and its subjectivity; and the third one referred to receptor.

Let’s have first a quick look at the work.

Joan Fontcuberta is a prominent Catalan photographer, well-known by his early and ironical works against photography as a truthful means to the world. Since 2004 he is been working, among other projects, on Googlegrames. The technique is quite popular nowadays: the user picks up a picture –let’s call it the ‘icon’- to be recomposed by a freeware –MacOsaiX-, which uses the Google image search to find a concrete number of pictures (hundred, thousand, ten thousand, etc) –let’s call them the ‘key pictures’-decided by the user. Then the freeware will download and use the key pictures regarding qualities like contrast and colour and use them like pixels to build the original picture, the icon. This is interesting to remind that the user can decide the search criteria under which the machine will find the pictures. This means that, while the first picture, ‘the icon’, is picked up directly by Fontcuberta itself, he only has a mediated and remote control on the secondary pictures –let’s call them ‘key-images’.

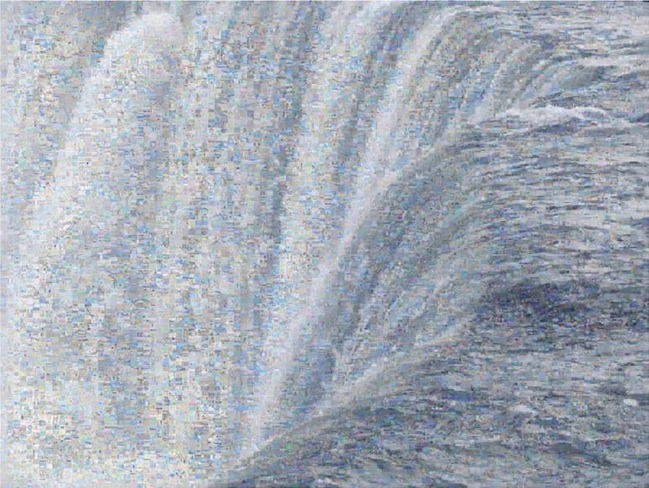

We can easily observe this features in the work Niagara, from 2007, built up from thousands of pictures that the Google machine found under the name of the fifty Nereids.

Except with this one, up to now I will refer myself to pictures included in a show in the Gallery Mayoral in the spring 2010 under the suggesting title Resilience.

I. Picture

I would like first to reflect a while on the nature of the picture. Like the very same artist has stated [1], this technique reminds and emulates the ancient tradition of mosaics, in which images where built up with small pieces of metal or stones. However there is a big difference: while the tessera are small pieces without any meaning, the icon is constructed from other images.

This first feature brings us into a paradoxical situation: the picture as Googlegrame is not a deictic photograph of a fact like the orthodox theory of photography holds. This icon is the reconstruction of a picture through other facts. The fact is not only connoted by a picture, is reconstructed by many other facts. We are now beyond the semiotic theory of denotation and connotation [2].

However we cannot grasp the complexity of the picture until we do not take into account the whole process of building the icon: the key-images have been picked up after a linguistic search. Since those key-images are not facts in the last stage either, but signs of words, this means that a level in-between has to be interspersed. Like Magritte’s “Ceci n’est pas une pipe”, in a first stage a Googlegrame reminds us that this is not a denotative picture and, following Foucault, that language is mediating the act of representing things. Furthermore, language is mediating the possibility of having representations, of having pictures [3].

The linguistic nature of the search has tempted some critics think on a first, too simple conclusion. The project of Googlegrames show that pictures are not deictic pictures of the world, but a sort of vicious circle that never ends going from pictures to words and from these to pictures again [4]. If we are to take Fontcuberta’s work as paradigmatic, following this, could we conclude that digital photography cannot be anymore understood as a deictic image? That words are involved in their construction?

This question would be perhaps too naïf. Susan Sontag already argued this conclusion some decades ago in “On Photography” talking still on analogical photography. However this hypothesis would likely be not only naïf, but at least slightly wrong. I will introduce now an example to try to explain myself better:

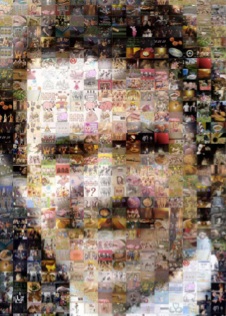

I would like to have a look at the relation among the key-images, the icon and the key-words. The next picture is called Maligne: (or “Evil”) and was built with 10.000 images found in Internet with a search criteria that includes words of demoniac forms and evil divinities like Abadon, Abraxas, Alastor, Alveo, Angat, Ariel, Astaroth, Belcebú, Caronte, Hades, Mefistófeles, Moloch, Murmur, and many others.

The search introduces a mechanical relation of causality between key-words and key-pictures, but this causality is indeterminate and arbitrary: as you know, Google search for images do not discriminate among pictures, and there are infinite reasons to join texts with any kind of pictures. This picture confronts us, on the one hand to a radical ambiguity of language in the net that can only conduct to unpredictable and arbitrary results. The patent disparity between key-images and icon leaves us with the frustrating conclusion of an essential heterogeneity between key-words and icon.

Now we can see here the reason why the key-images, the words and the icon do not draw a vicious circle. This is not so, but a cul-de-sac where meaning seems at the moment being inaccessible or, still worse, destroyed.

Fontcuberta himself has already pointed out the inherent theoretical problems that this conclusion has to a theory of archive, something that has always minded him. In my opinion, the consequences could go much further. I will formulate them in questions:

Following the last arguments, should we conclude that the gap between discourse and pictures is in the age of digital images insurmountable? Is our digital world the result of a very arbitrary, occasional, indeterminate relation between words and pictures?

If this is so, and taking into account that the contemporary representation of our world is nowadays digital, our conception of truth and knowledge would be dramatically affected. Many Fontcuberta’s projects work on the idea of showing those lies that pictures contain but often hide. Could these Googlegrames work on this sense? The relation between picture and world, could it be definitively expelled of the territory of truth and false?

A deep scepticism or even worse, a deep phobia against images as informational entities about our world is expanding socially. The topic that people believe what they see in TV is old-fashioned and obsolete. The next challenge of image professionals and thinkers is not any more to show that pictures are particular points of view and not absolute truths. The enemy to fight against now is the epistemological nihilism or radical criticism against representational images, which are everyday more taken as mere subjective creations. This leads us to ask about the role of the author.

II The artist

In this section I will deal with a couple of topics regarding the artist. I am not here interested in discussing some of Joan Fontcuberta’s suggesting reflections about his work. He has already talked with authority about the relation between Googlegrames and mosaics, he has already described the technical development that makes them possible, and he even has already talked about its relation with the notion of archive [5]. I am rather interested in the relevant presence of an artist’s subjectivity in this kind of work as well as the notion of creativity.

I have said that these pictures show a deep gap between language and icon and even key-images. Now we could ask whether this gap comes from an intermediating action of the artist.

You can easily detect this subjectivity taking into account the key-words for the search engine. As we have seen in the last example, the work Maligne shows no objective relation between the represented fact and the mythical. If we ask ourselves why the artist decided to use those words, we could easily deduce that the relation between words and key-images is subjective and capricious. But we can try to analyse this issue more carefully. What could be said of the intervention of a subjectivity in these works?

Romantic criticism asserted that works of art renew the relation between words and images in order to exteriorize an inner original world created by the artist, which had to be delivered to society. Even if this concise definition of creativity seems a bit ridiculous and superficial, it is growing up in a significant part of today’s digital creation. I am far away to hold this idea, though I do think we must consider a sort of creative intentionality in all digital photography. I will retake this idea later.

I would like now to consider a more sociological perspective, taking the point of view of the ideological criticism or even the discourse analysis. From these traditions of criticism, the determinant semantic relations established between icons and words are not the explicit ones. What is attended from a critical point of view are those ideas implicit in our ideological discourses, ideas that are usually unconscious to us but projected into social icons. Art can whether submit the dominant ideology or on the contrary reveal it through particular strategies. Following the critical theory some privileged critical artworks, by making them explicit, denote and denounce those prejudices or stereotypes that are inherited in the dominant ideology.

We can read Fontcuberta’s Googlegrames in this sense. The pictures Fontcuberta takes from the net, like the ones related to tortures in Abu Ghraib, to the Irak war and other media phenomena, are such social massive icons. He uses also Google’s software Zeitgeist to check which issues and pictures are mostly followed by our global community, taking what could be called metaphorically a radiography of humanity’s mind [6]. In this sense, if we retake the hypothesis –from the first section- that he shows an insurmountable gap between discourse and icons, we could interpret that he might be deconstructing the ideological discourses hidden behind icons. We can illustrate this with the example taken before.

When we see the pictures like the one used for Maligne in TV, we morally ascribe to it a negative value through the background and precedent knowledge of what evil means. This knowledge is inherited from both our religious and secular traditions. Taking this into account, Googlegrames could show some of the stereotypes sublimated in these new global icons. The key-words could manifest the implicit origins of what the humanity was thinking through these concrete pictures.

A second point to reinforce this hermeneutical thesis is to take into account the relations among Fontcuberta’s pictures and other works brought up in the show Resiliencia. In this exhibition, each Googlegrame was confronted to a work belonging to the private collection of the Gallery Mayoral. All of these works were related to the Spanish informalism movement and also to other political critical artistic phenomena of the sixties and early seventies. For our purpose it is worthy saying that the relation established between every pair of works is manifest through a formal, visual archetype; however, this similarity founds more deeply the ideological intentionality of Fontcuberta’s work.

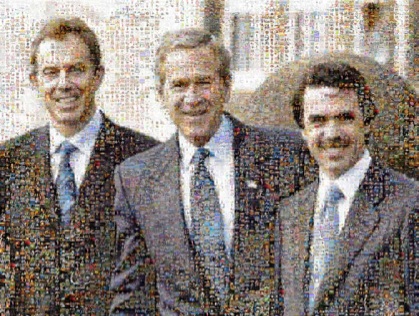

Hence, it is interesting and tempting to interpret Fontcuberta’s Googlegrames with this clue, but it doesn’t work either. In the case of Maligne, we do not necessarily accept that all stereotypes represented in the key-images are implicit on the production of the meaning. In other examples, this clue would work still worse or would not do it at all. Let’s take the work Irak. This picture, downloaded from the website rotten.com, shows a man with the head opened by a bullet. It is built with 10.000 images found in Internet with the search criteria of the names of those Presidents whose army participated in the Iraq war: Alfred Moisiu (Albania), John Howard (Australia), Artur Rasizade (Azerbaijan), and many others, among who are Jose Mª Aznar, George Bush and Tony Blair.

The critical task of the artist picking up such an icon and remaking it with pictures of presidents is not to reveal a social and ideological discourse. If we want to make work here the critical hypothesis, it has to adopt a wider definition, which has to combine precisely with a creative element. The picture brings an inherent and necessary semantic relation between an effect and a cause, in which the effect is the killing of people and the cause are the heads of states that supported and began the war. The effect and the cause are not any more evident. On the contrary, their link can only be accepted from concrete politically engaged positions, which, if they cannot be accepted as rigorously informational, they are quite plausible from a personal interpretation of the facts. We find here still the topic of an artist revealing hidden relations of a cruel reality. We find still an artist that, if he does not unmask truths, builds connections –more or less creatively- among far distanced facts.

However, we have to ask ourselves again whether this is definitively the general role of the artist in Googlegrames. I would like to consider briefly my favourite example. Trio shows the famous Azores head of states Bush, Blair and Aznar. The key-words introduced in the search for the key-images are famous trios or figures that have three elements, like: the three pigs, the three musketeers, the three graces, menage à trois, holy trinity, the three wise men, trio matamoros, trio calaveras, in Catalan, Spanish, English and French. We do not need to say that the new re-authored icon is dealt with the significance in our culture of the number three and the importance of trio groups to be able to achieve great challenges.

This is from my point of view, what Linda Hutcheon’s would define a typical Postmodern work. Hutcheon analyses the function of parody in Postmodern culture: it includes the Modern phenomena and at the same time its parody. Following this, Trio Googlegrame would illustrate the meeting of the three supposed governors of the world and parody it at the same time. The parody as critique is not a serious argumentative critique, but a critique that also puts into brackets the efficiency of argumentative discourses. Therefore, Trio includes the critic of ideology and the parody of this critical position. If we remind the relation that the very same artists brings with some parodic works like, for instance, those of Equipo Crónica, this sort of interpretation gains a lot of coherence.

The last makes us consider whether this work does not abolish the critical perspective we were presupposing in Fontcuberta’s intentionality. We must wonder whether this is still ideological criticism or rather a sort of self criticism that shows the impossibility of a strong criticism. Is this Googlegrame reducing into absurd the ideological criticism? Is it just parodying it, like a kind of Dadaist work would do?

In this second section we have seen that, taking Googlegrames as a model of digital pictures, there should be considered, first, a creative element that remakes other’s discourses; second, and as consequence of the first, a relation to social or ideological issues and, third, eventually a self irony, a self-critical point of view. What is however the goal of this critique? As we know, understanding critique and parody has much to do with the receptor’s point of view. We will turn to this issue in the next section, in order to bring together all the earlier conclusions.

The spectator

Most of Fontcuberta’s Googlegrames point at the so-called “big discourses”, serious topics or even, like our sexist grandparents used to call, male issues. These are politics, war, religion, immigration, evil, etc. Among Fontcuberta’s topics, it just lacks sports, but if they really hold male issues there will soon likely come some Googlegrames on Guardiola, Messi and, why not, Mourinho with Tito Vilanova.

We tend to think that this sort of topics is socially relevant and serious. I am sure that works of art that deal with these themes have socially such added values, even if this is not an advantage at all to compete with decorative art in the market. However, in what we have seen, we can argue that Fontcuberta is not developing any sort of big discourses. We have already discussed that we cannot deduce a clear critical intentionality regarding ideology, since some self-irony is also present. Why is then Fontcuberta interested in dealing with them?

Some could also think exactly the opposite, that is, that he is taking advantage of the popularity of these icons. This would slam Fontcuberta’s work as using the spectacular condition that some images have acquired, being the author an accessory of the spectacularisation and banalisation of such issues in the media. Some works on Abu Ghraib, on peace and on ecology, could be interpreted in this sense. However, what we have said in the previous sections, regarding the nature of the work and the intervention of the author’s subjectivity should make the receptor suspect that, if this can surely be true, there must still be more double meanings.

On the one hand, regarding the work’s ontological condition, I have said in the first section that the pixelization of the icon through thousands of visible key-images and through the mediation of language destroys the univocity of the work and breaks the logical consecution of a meaning. It manifests the disparity and heterogeneity of the iconic elements, which therefore seem not being able to build the image they are actually building. In this constantly approaching and taking distance of the picture, the digital pictures show themselves epistemologically ambiguous and unsuccessful.

On the other hand, some considerations on the author have shown that digital pictures inherently include a reinvention of reality that avoids old dichotomies like analytical or creative works, ideologically neutral or critical positions and funny or serious attitudes. These pictures deal with the topics they represent but through a more distanced manner, in which an orthodox critical discourse -on ideology, for instance- does not seem to be possible any more.

The very nature of these works makes the viewer take a hermeneutic position in two levels: first, he has to ask himself about the topic that the picture represents and the parodic context that the key-words and key-images build as background. But the receptor has unavoidably to ask himself on the means through which these topics and discourses come to exist, that is, on the nature of the pictures. Googlegrames invite us to revive our experience as minded spectators of these images in their original source. Googlegrames make us revisit the voyeuristic situation in which we got in contact with these images and wanted to feel morally disturbed, they make us feel again the contradictory feeling of being minded but also unconfessed curious and ghoulish spectators.

If we take Googlegrames as overstated models of digital pictures we could perhaps question whether the new –digital- nature of photography could bring the viewer to the opposite effects that realistic photography had in the 20th Century. If analogical photography presented itself as a prove of a fact, hiding the ideological discourses inherent in it, will the new photography make the viewer be more aware of his own scopiphilia by making him doubt of the reality that pictures represent?

Notes

1.- General remarks on his own work can be founded in his webpage www.fontcuberta.com, more specifically in his own article “Archive noise”. Last looked up 30th August 2011.

2.- Let’s say this against what other authors have stated: see for instance: Iria Barcia & Enrique Barcia, in “Del mosaico al Googlegrama: posibilidades creativas de la interacción imagen texto”, Tejuelo. Revista de Didáctica de la Lengua y la literatura, Núm. 5, Año 2 (2009), Junta de Extremadura; and also Joana Hurtado Mateu, “El trau de la taca o el conflicte de mirar”, in Resilience, catalogue show, Galeria Mayoral, 2010, Barcelona.

3.- Foucault, Ceci n’est pas une pipe, Montpellier, 1973

4.- Joana Hurtado Mateu, “El trau de la taca o el conflicte de mirar”, ib.

5.- See previoius note.

6.- See Fontcuberta’s reflexions quoted above.