The Shifting Condition of Art Discourse: an Interview with James Elkins.

Loredana Niculet

James Elkins is a prominent Professor of Art History, Theory and Criticism at the School of Art Institute of Chicago, and a prolific author, with nineteen published books and numerous works in progress. Furthermore, he is required reading for both postgraduate and master courses in the arts, in the United States, as well as in Europe. I would like to emphasize, from the outset, his authentic meta-critical predisposition towards his own discipline as well as his openness towards Non-Western modernities and postmodernities. A good example of this is the most recent book edited by James Elkins, Art and Globalization (Pennsylvania State Univ. Press, September 2010), an ambitious project of rethinking contemporary art from the perspective of the complexity of artistic production on a global scale. What follows is an edited transcript of an interview that took place at SAIC (The School of Art Institute of Chicago) on October 19, 2010.

Loredana Niculet: I would like to begin by establishing three referential topics of the dominant debate in current art theory: the crisis of art criticism, the hegemony of Western discourse and the necessity of new fields for aesthetic research. In What happened to Art Criticism (2003), you attracted the attention about the ubiquity and at the same time invisibility of art criticism - “art criticism is massively produced and massively ignored”, just as art itself, we could say. One of the main causes of this paradoxical condition is the so-called “academization” of critical thought. Many of those who have worked initially as art critics, started being interested in art history and retired strategically towards the academic “monasteries”, against the disproportionate protagonism of the museum – as global institution – and the fast ascent of the curator – as new manager of the artworld. Have we sufficient reasons to think – contrary to Spinoza who, in 1673, refused a philosophy professor position in Heidelberg, because he believed that the academic system would affected his freedom of thought – that today in the academic field there are less restrictions on thought than in other fields, more exposed to the cultural industry?

James Elkins: It’s a very interesting opening question, and so is your whole perspective on the public, the private and the institutional and non-institutional. On the one hand, I think that your interest is very broad - so you’re talking about what would we call in English “public intellectuals” – and on the other hand, I think your interest is also very specific – in your dissertation, for example you’re talking about one small group of producers of art. Your opening question is extremely broad, and yet your research is sharply focused: an unusual combination [1].

I’m happy to try to go back and forth between these very general socio-political questions of liberalism and neo-liberalism, and conservatism, on the one hand, and the much more specific questions of your own work, on the other hand. But I’m also concerned that we find bridges between these differently scaled arguments.

It is easy to say that academic art criticism has no effect on the outside world, as a generalization. Obviously, there are counter-examples, but in general, academic criticism has little effect. And within academic art criticism you can than speak of several different kinds: the kind that you study - the art journal October - is ultra-academic; it’s at the heart of the heart of the academic discourse in relation to the arts. And then outside of academia you have a number of people who are writing more or less thoughtfully about art. You have a lot of specifiable, semi-academic kinds of writings before you get all the way to the newspaper journalists and the people who write catalogue essays—and even there, I think, you would sometimes have a hard time arguing that politically motivated writing has a measurable effect. So I would prefer to divide the dichotomy academic/non-academic into several more specific sub-categories in order to make progress on this question.

LN: Although it is true that the university is the place where most part of the projects of critical thought are generated, it is also true that it has stopped being a politically relevant agent in our society. I’m thinking, by contrast, in the student counterculture of the late sixties.

JE: So again, I’d want to make a distinction between the general question and the specific case of October or academic art writing. Concerning the general question: in the late sixties protests took place in difference universities in several countries—in France, in Mexico, in the United States—and you could argue that those protests had many different effects on society. They were certainly widely watched and widely commented on, but if you look at the same time period in art and in the academic discussion of art, I’m not sure if you see any specific effects of those protests or the student movement in general, and this goes directly to your subject concerning the October circle and the moment of “anti-aesthetics.” As Hal Foster said in July 2010, when he was here for the book I am editing, Beyond the Aesthetic and the Anti-Aesthetic [4], “we were all just some kids in Manhattan.” So you have a very stark contrast there between the interest that some artists, critics, philosophers, and theorists had at that time in changing society, and what they actually did. What would be, from your point of view, a good example of a political effect that art made in the late sixties had on society?

LN: I was rather thinking of the kind of practical effects Foucault’s ideas have on feminist and gay movements.

LN: October´s first decade, maybe? They were talking about art writing in terms of a practice, even in terms of “an avant-garde continued by critical means”…

JE: But what effect did that theorizing have on general, cultural perceptions or configurations, others than the notorious and largely unanticipated effect that it helped to isolate academic talk? As you can see, I am fairly pessimistic. I don’t see the political efficaciousness, the political viability of most poststructural political art and I don’t see the political effect of the theorizing that went on in and around October in its most important first decade. What I see is that October consolidated, retracted, and compressed a certain kind of academic discourse, taking it further and further from the general public life in North America, instead of bringing it closer. There is now an enormous literature about how art connects to society, but there are very few examples of art that has actually persuaded people, that has changed their minds. The great hope that some people have in - Jacques Rancière is an example, for me, of the desire to find a forcible link between art and politics. The publics of postmodern political art have been self-selecting: they already know the messages they receive. That is why I find much of Benjamin Buchloh’s work to be trenchant but pathetic (full of pathos).

LN: The relative physical isolation of the campus, in the case of many universities in the United States, has been seen as a symptom of the social isolation of the academy (or of the distance, as Habermas would say, between expert culture and life).

JE: I would just be a little careful about that because there are plenty of counter-examples. I mean, you’re talking now in a city where there are three universities right in the urban center.

LN: That’s true, I was thinking about the typical university campus which is a city per se.

JE: Maybe, but I just be careful about that. They do exist, Princeton is the major example, because it’s off by itself in a relatively small place. Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, where I was born and where Hal Foster used to work, is a small town, but it’s half an hour by plane from New York. I’d be careful about that argument about physical isolation. But I wonder, in your terms, if what’s going on here is that, paradoxically, the same politics that generated changes in society in other fields, had the paradoxical effect of making the art world smaller and less powerful in relation to the world at large.

When you put the question that way, when you say that critical thinking is generated within universities, you have to ask what you mean by “critical thinking.” One of the major models for “critical thinking” is Adorno’s Marxist critique, and another model is the Kantian Kritik. In other words, you’re applying academic criteria to your judgment about the superior position of academia. You could say instead that many interesting ideas happen outside of academia. So the way you put the question might make it difficult to answer in a fair way. Instead of saying “critical thinking,” you might say, for example, “innovation” in art practice or discourse, in which case you probably can’t say it happens mostly in universities, you would probably than have to say it happens in other places as well.

JE: Well, there isn’t an easy solution, because first of all, there’s no clear call for “normativity”. If there were a clear call for any defined position, then it would be possible to answer this call. The call seems to come from within a certain understanding of critical theory, within this understanding there is now a gap or a deficit and this has to be somehow addressed, but the call doesn’t exist in many other arenas. For example in the public sphere, readers of newspapers, the call doesn’t exist. So I guess I would want to turn that question around and ask the conditions under which you would want to think that there is this necessity. This is, to my mind, related to the kinds of things that Hal Foster has said about rethinking the spectacle: there are things involved in the homogenization of the spectacle that make it impossible to understand actual individual practices and critical discourses. Whereas if the spectacle can be just a little bit dismantled, if distinctions can be made within it, if other forms of agency can be seen to be acting, and maybe, even if they’re collective forms of agency that we might we want to reject at first, we might avoid obscuring a whole range of phenomena. So, in the same way, in this case, the call for something to address, this deficit or this lack is something which is self presupposes, a monolithic kind of understanding of critical thinking and judgment.

LN: I was thinking, in relation to this idea of normativity, about the debate on the cultural canon, which seems to have renewed itself after a period of time in which Derrida’s anticanonical discourse was predominant. I’m thinking of Harold Bloom’s book The Western Canon (1994) or of Pierre Bourdieu’s Homo Academicus (1984) and even of the more conservative tendency, in recent years, of discourses like October’s, which arose, at the time, as anti-canonical alternatives. Is that because the academic canon implies, besides order, structure and previsibility, a political dimension, particularly remarkable in the global culture?

JE: I would put this question slightly differently with slightly different examples. To me, Harold Bloom is an eccentric choice. Pierre Bourdieu raises other kinds of questions; I’m not sure, for example, to what extent you could claim that he represents a return to a canon. So I would use different examples. For me, the examples would be the return to beauty: a book by Elaine Scarry, called On Beauty and Being Just; a book by Wendy Steiner on the gendered nature of the sublime and its relation to beauty; and a text by Alexander Nehamas, in Art History versus Aesthetics. There is a constellation of maybe a dozen texts in and around this question of beauty. Even though some people doubt it, I think that these texts are fundamentally conservative. So that’s the context into which I would place your concerns, given that I’m not sure if there is a return to a normative canonical pedagogy. Even these texts are quite different from one another. On the other hand, you can argue that they are constitutive and important for the future if you add to them texts like Relational Aesthetics. If you broaden the field a little so that you’re talking about books like Bourriaud’s, then you’re close to naming a major new direction of the artworld, to a consensus within the artworld about a new direction: and in that case, it does seem to me that there is a politics.

LN: … of the ‘minor’?

JE: Of the minor?

LN: If these directions are marginal in relation to a more generalized discourse on art, than we can talk about a politics of the minor?

JE: If they are. But also, at least for the young art students whom I see when I travel, things like Relational Aesthetics and its more or less open formalism and skepticism of major political change are very attractive. I would almost say a majority of younger artists and art students who are completing their education hold to some version of ideas like Bourriaud’s, if not ideas related to the group of texts that center on beauty and the sublime. I don’t see that as a canon building and I don’t see it as a return to a period before poststructuralism, because those artists are afraid of canons, they don’t want canons, but they are nevertheless interested in a return; there is a sense of an historical return to a less ambitious politics, a politics that can be efficacious in everyday life, or a politics that can be done on a very small scale. In politics as it’s imagined in relational aesthetics, you don’t try too hard, because you can’t do too much. It is, in that sense, a politically flavored, apparently formalist, cryptically aesthetic conservatorism.

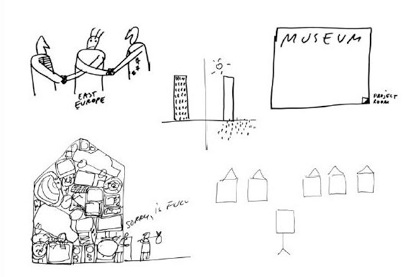

LN: ‘Postmodernism’, ‘pluralism’, ‘liberty’, are often used as excuses for “anything goes”. This situation is clearly seen in the case of most of the post-Communist countries in Eastern Europe, where the end of the old regime was quickly replaced by the triumphalism of global capitalism. There is a tendency to reject re-thinking the past meanwhile embracing uncritically, unconditionally, a certain standardized capitalism, including the Western system of contemporary art. (“Don’t Marx me” is a phrase used by a Romanian artist, Dan Perjovschi, to allude to this situation) Cities like Bucharest - which you have already visited - became postmodern before becoming really modern. The tension between post-Communism and globalization is easily recognizable here not only in urbanism, but also in the generalized political indifference of the citizens. These social particularities seem to have encouraged new forms of political art, which in Western culture appeared to be exhausted. You’ve already advanced your position about political art, but I will still formulate the question. Do you think that political art could really inspire critical engagement with social factors?

Dan Perjovschi, “What happened to us”, Project 85, MoMA (2007).

JE: So if you put it that way, if you just ask your question without a frame, without a preface, then yes, my answer is very pessimistic: I think, in general, the answer is no. I did spend a fair amount of time looking for examples when we were working on the 2007 Stone Summer Theory Institute Art and Globalization. I led a seminar in which students searched for the most politically powerful interesting works that they could find. We did special papers on the critical reception of art projects such as the Critical Art Ensemble and the Yes Men. And it’s on the basis of the critical reception that I feel skeptical: not that these projects can’t work, but that the public on whom they work has already been convinced.

But, if instead of asking that last question, you’d just given me the preface to the question, I would say there are a lot of interesting things to be said about the condition of post- Soviet countries in relation to conditions of Western Europe and North America. There are to my mind very interesting parallels to be made. In North America, in the eighties, an apolitical art - Neo-expressionism - was suddenly confronted with an intensely political art - Anselm Kiefer’s - and that encounter supposedly initiated a revival of political commitment among a number of artists and artists’ groups. But the political commitment at that point was no longer aimed as exactly as it had been in the sixties and seventies, because there had been a hiatus of carelessness, political disengagement. As everyone knows, the political art in the late eighties and nineties had become very predictable in its ideologies, even if it had also become less predictable in its strategies, which continually had to be reinvented in order to provide the appearance of efficacy. I think of this, by the way, in relation to Hardt and Negri’s Empire - as the empire grows more intensely machine-like, as fewer and fewer spaces remain, the strategies have to increase in speed and flexibility, but at the same time the aim of political intervention will narrow and become easier to discern.

So to me the parallel is with post- Soviet countries, where, as you say, there was a gap which you could call modernism or late capitalism, a gap into which suddenly flooded a sense of internationalism, creating, from a Western European or North American point of view, an odd mixture. Hence some art practices in Eastern Europe can seem uninformed in the way that certain North American practices of the 1980s (such as Julian Schnabel’s, for example) seemed uninformed to an East German or a West German critic of the eighties. In both cases there was the feeling of an historical absence.

So, except for the last part of your question, I think there are a lot of interesting possibilities for dialogue, which could result in new kinds of political practices. The vehicle for that dialogue, I think, is historically informed comparison.

JE: Do you believe that, by the way?

LN: I do not know if to believe it or not. Maybe today this kind of anachronisms could appear as ironical, but then, it were perfectly representative of the policy of the cult of personality of the national leader. What determined you to attend to that auction?

JE: I’ll answer to that last question first. I went to that auction not knowing what to expect and I was absolutely amazed that how enormous it was (I still have the catalogue). For me, the value of the experience was not so much the artwork, because most of the objects in that auction were not artworks. For me the value was hearing from the woman who ran it that they had sold everything offered in their previous auctions and they expected to sell everything in that auction, which showed to me the enormous nostalgia for the regime - because obviously these things were only selling within Romania. Where else would they sell?

In terms of whether or not this artist, Hatmanu, could be sincere: this reminds me of two scholars: Boris Groys’s writing about Soviet Stalinist era art; and the Chinese scholar Cao Yiqiang, who works in Hangzhou in China, who was written about Mao era art. Groys’s and Cao’s arguments are parallel, because their claim is that a certain number of the artists in those regimes experienced their condition as freedom. Such artists were therefore not only being ironic, and many were without irony in this sense. Apparently, the Romanian artist - whom I don’t know - would want to contest that. Clearly, these days, you don’t want to say that you were un-ironically following the dictator, but at the time, it seems historically not unlikely that a large percentage of the art made under these regimes was actually made in a condition approaching the appearance of freedom from the artist’s point of view. That would be my guess, but how would you go about proving it? You have to prove it by letters, by documents from the time, right? (laughing)

LN: If I’m not wrong, compared to those art critics who emigrated from the journalistic practice to the chairs of art history departments, you tried the opposite: to get out of your own academic condition, into the world.

JE: Again I feel like I should make some sort of preface or framing remark like I did at the beginning, because I don’t see this as being a question of academic positions versus the real world. I see it as a question of several different positions within the art world, but I would understand “the artworld” very broadly. I have an essay which you may not have seen called “Two Modes of Judgment: Forgiving and Demanding.” It’s about marine painting, painting of boats, in North America and in Leningrad. The point of this essay is to ask how far can you go outside of academic positions in relation to art and still be talking about art. In other words, you can escape from the question of art by talking about science or illustration. But within the artworld, what is the farthest you can get away from academic interests? Tourist painting is one possibility, and within it I chose marine painting. I wrote this essay about two schools of marine painting, done in the Northeast and Northwest coasts of the US, and in Leningrad. In Leningrad, they have a continuous and strong tradition of marine painting from Impressionism to the present.

So the point of this essay was to say the following: that when I travel, I mean physically travel, to these places and see the practices and talk to the artists, I have a very forgiving mindset, in other words I want to understand things from their point of view. If someone shows me a terrible painting of a fisherman’s boat, I still want to talk to that person and find out how do they understand their practice, who did they compare themselves with, whether they have a gallery or just give their paintings to their family and friends. In other words, I’m very empathetic.

On the other hand, when I’m judging things from the point of view of academic criticism, say from October, I would never go near marine painting, I would never go anywhere outside of Academia: marine painting would be, from that point of view, at the other end of the universe.

So here’s the idea: my argument is that in the discourses of 20th century or 21st century painting, there is no middle ground, no way to be between “forgiving” and “demanding.” A person like Benjamin Buchloh is extremely self-consistent, he has a stable critical position. A person who knows a marine painter in Nova Scotia, say, can also have a stable position if such a person can get their paints and go out on a Sunday morning and look at the ships and paint them and go home and show to their family. Such a person can be perfectly happy, and such a practice can be perfectly self-contained. Those are two stable positions on far ends of the spectrum. The problem is that there is no stable position in the middle. I will explain what I mean by that. If the painter in Nova Scotia, say, looks across the harbor and sees another painter, then they could start comparing their work with the other painter and want to know how good that other painter is. If they start talking to the other marine painters, and acquire a wider circle of comparisons for their work, they may even decide to compare themselves to the Marine Painter’s Association of America, maybe even the International Society of Marine Painters (www.ismpart.com).

At that point, such an artist could say: now I understand that I’m the best marine painter in the world, but what about other kinds of painting, like paintings of horses and dogs? I like them too, and maybe I’ll start comparing myself to them too. And then I might think even more broadly, and start comparing myself to the entire tradition of realist painting. And if I do that, then I’ll wonder what happened to realist painting. The person I am imagining would then have some anxiety because she’d realize realist painting is in jeopardy. Maybe she’d want to move on and compare herself to the tradition of abstract painting. But then what about the question of painting itself, and the death of painting? Maybe those should be taken seriously as well.

So, this is what I mean by saying there is no stable middle position. You have to be either on one end or the other. I think the whole shape of art discourses in this respect is like a slippery mountain. You slide down to one side or the other. In a way, positions like Benjamin Buchloh’s are safe and very provincial, and in the same way the marine painter’s position is obviously provincial, blind to the rest of the world, but very stable. (There, that’s an unusual argument for you: a structural parallel between Buchloh and marine painting.)

In regard to what happens when I try to step outside of these academic situations: I don’t think it’s a problem to step all the way outside; the problem is to see the shape of the discourse as a whole and to try to speak in such a way that you can speak from some moderate position that’s in between the two.

LN: As an anthropologist?

JE: Well, if you’re working as an anthropologist, you erase the problem because an anthropologist doesn’t care about qualities or aesthetic value. In that case you have no issue, it’s very easy.

LN: Coming back to the anachronisms of official art. Another curious detail in the official painting we mentioned before is the presence, behind Stephen the Great, of the Palace of Culture - a Neo-Gothic palace built by King Ferdinand almost 500 years after Stephen’s reign. Two incongruous moments of the national past were retrospectively brought out together in order to legitimate Ceausescu’s regime as a heroic age. Another contradictory scenario, in the present, would be the location of the National Museum of Contemporary Art of Bucharest in one wing of the “People’s House” (‘Casa Poporului’) - Ceausescu’s former residence and actual Palace of the Parliament.

JE: Too bad the museum doesn’t occupy the whole palace!

LN: Nevetheless, the MNAC opening in 2004 has caused – and still causes - controversy in the local artworld: if for some, this incongruity is an exceptional example of post-communist solution, for others it is the result of a political and propagandistic strategy. Yet, isn’t the museum of contemporary art a contradiction in terms?

JE: Again, I would like to separate your question from its preface. A museum of contemporary art is a contradiction in terms, if by “contemporary” you mean only the art of the present; but I think we can talk about that in a minute. About the preface to your question: I think it’s a custom in the construction of contemporary art museums to put them in politically unlikely places as a token of the new internationalism. So, you have in Ireland, in Dublin, the IMMA, the Musem of Modern Art; it’s in an old army barracks. (There is an entire university, by the way, in an ex-army barracks: the Jacobs University, outside Hamburg. Its buildings were Nazi era barracks, and the part of the Humanities is in a big building that used to be a garage for tanks.) So I don’t think propoganda or politics is an issue in this context, I think it’s almost to be expected now in the construction of new buildings. By the way, isn’t there a museum in Bucharest which has videos and memorabilia of Ceausescu’s regime? When I visited it, there was a small museum and they showed on a video monitor television from the Ceausescu era - nothing but parades and speeches of Ceausescu and they had memorabilia. It was very arch, ironic, and postmodern, that kind of thing that is now rendered obsolete by the sitting of the entire contemporary art museum in a palace. (laughing)

LN: How would you define the “contemporary”? It’s rather a question of calendar (i.e. anything is passing now, is contemporary), a (post)historical condition (like for Arthur Danto) or on the contrary, is the contemporary an always raising condition, a pure virtuality?

JE: I think that last of those options is true but is not sufficient as a way of talking about this problem. I don’t subscribe to Arthur Danto’s position because it’s too un-modulated, too sweeping. There is of course a big literature on this; there is a new book by Terry Smith on global contemporary art, for example.

Hence instead of trying to choose the best theory I will propose two additional criteria that maybe haven’t been talked about so much. One of them, for me, would be that something is contemporary if you can attach it to its region, country, or area - but at the same time it is not problematic to imagine placing the work in an international art fair. If the work is done in a specifiable region but at the same time it would be impossible to imagine it in a biennale or in an art fair, than I would say that’s modernist. It’s the very condition of modernist work to remain isolated in this particular way, because of the universalizing claims of modernism, which reject so much of the world production of art, presenting it, as you know, as belated or marginal.

A second way of thinking about the contemporary, which is also not often discussed, is that the contemporary would be that period in which art historians, theorists and critics started to worry about the globalization of their own disciplines. When I was in Buenos Aires someone told me that when Clement Greenberg was there - I believe he visited it twice, by the way - and he was about to leave, he said to his host: you could have modernism too if you want it! (laughing) In that attitude there is no anxiety about globalization, in this case of art modernist practice; and by the same token, in art history, until about fifteen years ago or so, there was very little debate about the worldwide spread of the discipline of art history. Now the debate is become intricate because of self-reflexivity about Westernness, and about the inevitable of political valence of any kind of globalized practice.

LN: You have approached a great diversity of topics – from the connection between Renaissance and Modernism (Renaissance art was the subject of your PhD dissertation), to the historiography of art history and the challenging of art criticism in the era of globalization. An area of special interest for you is the connection between science and art. I’d like to mention here your introduction to Eduardo Kac’s book Telepresence and BioArt. Networking, Rabbits and Robots (2005).

JE: Is that translated in Spanish now?

LN: Yes, it has been published this year in the ‘Cendeac’ Collection. In order to approach all these subjects, what was your methodological parti prix?

JE: I know I should have one answer to that and I know that my general profile in scholarship would be clearer if I had just one answer, but I don’t, I have different kinds of answers. The closest I could come to a single general response is that I’m not convinced by the ways the discipline of art history draws boundaries. Most of these boundaries, it seem to me, are not necessary even according to the internal logic of art history itself. Some of them, for example the boundary between art and non-art is an inbuilt boundary within art history because art history is fundamentally a historicized response to aesthetic determinations and therefore, if you step outside of that realm of objects that were originally received as aesthetic, you step into another realm of inquiry. Therefore most of the things I’m interested in are outside of normative art history, but not all of them are proscribed by the discipline itself. The discipline itself has no reason to exclude marine painting or that lovely painting of Ceausescu and his wife, but the discipline of art history does have legitimate reasons to exclude science and non-art images. There are two different forms of exclusion, both of which I find interesting.

For myself I’m often not interested in art per se. I know I’m not supposed to say that as an art historian. Sometimes I’m very interested in art but a lot of the time I find that what I am interested in is the visual world in general; and from the point of view of that kind of interest, art history really is the way that people like Mieke Bal see it: a very narrow, politically overdetermined, and now ancient and hopefully dying discipline. (laughing)

LN: Is it possible that the new media related to the Internet are indicative of a new era, substantially different from the previous postmodern age, which was basically an era of mass consumption of art? In this respect, Boris Groys recently affirmed (during the 1st “Former West Congress” in 2009, Netherlands) that the new networks like Facebook, YouTube, Second Life, Twitter, etc., give global populations the possibility to place their photos, videos, and texts in a way that cannot be distinguished from any other post-Conceptualist artwork. Could we say that more than massively consumed, will art be massively produced?

JE: Boris is very much a provocateur and he’s both problematic and fun to argue with (laughing). The claim - as I understand it, because I haven’t heard him make this claim, but as I understand it your summary - the claim would be something like this: What’s happening out there with YouTube permits everyone to do things that Duchamp could only do by himself in the artworld. To me, this is more of a provocation than an interesting claim for the following reason: most of these millions or billions of people on Youtube would be completely uninterested and unenlightened by being described as ladder-day Duchampians. The force of Boris’s comment is to épater le bourgeois, if the bourgeois are art historians, because the art historians are the ones who want to claim that it was really Duchamp and that these other practices are importantly different. So I would like to try to keep Boris a little bit out of that question. The first part of the question was about whether or not new media actually represent a transformation. On the one hand, it’s hard to argue that they don’t, because Facebook has millions of people in it, etc., etc., and everyone uses it – just this morning, I’m trying to devise a trick on Facebook because I read that the interests (the “likes”) that you add to your Profile Page in Facebook determine the advertisements you’ll see on Facebook. I have deliberately put down some very strange interests so I can see what advertisements appear. (One of my interests is supposedly “Facebook ads that actually match my interests.”) So on the one hand, new media are transformative. On the other hand, there are many ways to argue that these things are not important transformations. A long time ago, I wrote an essay called “There are no Philosophic Problems Raised by Virtual Reality”, because virtual reality was claimed to be this paradigm shift and an epistemological revolution and so on. My general feeling is that the newness of these things is exaggerated. I’d prefer more of psychological critique. I would like to know more about the desire to claim that new media are transformative came from. Why do people need to attribute these philosophic properties to new media? I end up thinking more like, say, Walter Benjamin. In other words, there is an intense desire to believe that have somehow jumped out of the social configurations that we had been stuck in, and somehow magically landed somewhere else. New media enthusiasms are bit said, if you think of them this way.

LN: Let’s talk now about an issue you discussed sometimes: psychoanalysis. What would be for you the cultural basis for the use of psychoanalysis in art interpretation? I’m asking you this because in the case of many contemporary art theoreticians, the interest in psychoanalysis arose from an initial preoccupation with the problem of ideology, from a more general interest in Marxism, to be more precise.

JE: Actually I don’t like to use it in art interpretation myself. My main interest in psychoanalysis is to observe how concepts that are taken as optimal descriptions of the psyche are deployed by art critics and historians. The sense of psychoanalysis at animates the work of people like Kaja Silverman, or for that matter Hal Foster, entails certain recurring concepts that are taken to be crucial, essential, or optimal for models of the psyche, even though those same concepts are deeply problematic from the perspective of, say, clinical practice or psychiatry. The concept of the unconscious is the central instance, and then there are innumerable satellite concepts, such as repression, the integration of the ego, and so forth. I don’t actually believe in the psychoanalytic lexicon in such a way as to deploy it to interpret art (or actual psyches). I agree with a line in Derrida, in one of his essays on psychoanalysis, where he says, in passing, “we have never believed in psychoanalysis enough to actually use it.” In those moments when I find myself in agreement with constructions such as the objet petit “a,” than I turn the question of veracity back on myself.

So in that sense my engagement is also not political. In other sense, of course, it is political because there is a certain kind of liberal critical education in the humanities for which some of the conceptual forms of psychoanalysis are absolutely indispensable. I also agree with Derrida, in his exchange with Michel Foucault, where he says of Foucault, more or less, that Foucault’s entire body of work, exists inside of psychoanalysis, in the “age of psychoanalysis.”

LN: Do you see a historical connection between psychoanalysis and Marxism?

JE: Yes, to some degree. My attitude toward the truth value about psychoanalytic claims is a point of difference with like Hal Foster, in the sense that psychoanalysis is ultimately one of his principal points of references and grounds of interpretive sense, but of course he is an especially sophisticated example of what can be, in others, a relatively simple dependence. Nevertheless there are moments in his narratives when is it clear that psychoanalysis is the horizon of the interpretation and in those moments I find that I can’t follow along. I mention this because for me, a similarity between Marxism and psychoanalysis, aside from their traditional and often unanalyzed twinning in leftist poststructural thinking, is their common function as ultimate explanatory terms. For any number of academics, a chain of questions, an iterated inquiry, will lead to an interpretive ground that is identifiably Marxist. That ground, in the common and sometimes indefensible habit of poststructuralist thinking, is partly also psychoanalytic.

LN: No matter how interesting psychoanalysis could be, as theory of culture or as interpretative tool, for certain artistic practices like surrealism or feminism, it doesn’t say too much about the aesthetic dimension of art works. If I understand it well, your defending, in books like What painting is (1998) or Pictures and Tears: A History of People who have cried in front of Painting (2001), of old concepts like aesthetic pleasure – contrary to the tendency to legitimize art from an exclusive conceptual or political perspective – goes in this direction: the fact that an art work expresses certain psychological or political tensions does not explain its aesthetic value.

JE: Again, I see several different questions which I would like to separate and reframe differently. So from my point of view, enterprises like postcolonial theory which imagine the aesthetics content of artworks to be a product of social and economic conditions are at risk of producing counter-intuitive and a-historical accounts of artworks, because in the end they have to run against the artists’ and the receivers’ own ideas about the work. For example, if you’re going to talk about paintings done in the Tokyo Academy of Art in the second decade of the twentieth century as products of the socio-economic and institutional conditions of the Tokyo Academy of Art, you cannot then talk about the intrinsic aesthetic value that the artists of that time thought they were expressing. A socio-economic interpretation necessarily reconfigures aesthetic value as a cultural construction, and its ultimate terms of explanation are economic, social, anthropological, ethnographic, or otherwise non-aesthetic. I am alluding in the example to John Clark’s book Modern Asian Art where he does this from a postcolonial standpoint.

So to that extent I am interested in aesthetic value, but only because I’m interested in the fact a postcolonial theorist has to imagine that there is no problem in re-describing aesthetics as the effect of a preexisting economic condition. If people writing postcolonial theory also say “I recognize that there is something outside of my redescription”, something which resists my redescription, then this issue wouldn’t exist for me.

I am interested in studying the ways that aesthetic qualities have been forced out, rewritten and overwritten, excluded, or explained the way in various kinds of writing including postcolonial theory. But I’m not so sure if I would like to say that these books of mine, What Painting Is and Pictures and Tears, are about aesthetic value. I understand that the idea of an aesthetic value can be very very broadly construed but in the case of What Painting Is book, what I’m mostly interested in is materiality and whether meanings in general (not necessarily those that pertain to aesthetics) can be assigned to materiality. In the case of the Pictures and tears book I’m interested in a wide range of reactions, which from a Kantian point of view are non-conceptual, and therefore open to interpretation as aesthetic reactions; but it was never my intention there to make a catalogue of aesthetic reactions. Some of the reactions I discuss were understood by the people who reported them to be aesthetic, but most of them were not understood that way.

I think you could rephrase the first part of the question more strongly. You say that psychoanalysis doesn’t necessarily have much to say about aesthetics quality, I would say psychoanalysis necessarily has nothing to say about aesthetics, because, like postcolonial theory, it has to rethink aesthetics in terms of desire. Of course, there is the Freudian theory of sublimation and his notion of what art works were; for him aesthetics is a symptom, not an actual quality of an artwork—it’s a symptom that is construed or desired to be in an artwork. Psychoanalysis, in a strict sense, is completely separated from aesthetic evaluation. So those are three different evaluations to different parts of your question, but, in general, I’m sympathetic with the importance of interpreting aesthetic reactions that other people have, placing them in an historical context and understanding their conditions of reception. On the other hand, I’m critical of interpretive regimes that would claim that is a sufficient as opposed to a necessary move, because then the aesthetic claim on truth vanishes. So one of my projects on modernist painting called Success and Failure in Twentieth-Century Painting – an unfinished project – has to do with the fact that in order to understand the shape of 20th century painting it is necessary to take very seriously, at every point, the shifting conditions of success and failure as they were understood in different times and places.

Not to relativize values, but to say that aesthetic judgments are absolutely crucial and they have to be allowed as long as possible to stand on their own as long as possible, as they were intended and as they were received, before they are reconfigured as the symptoms or effects of received ideas, class structures, economic conditions, social contexts, and so forth.

LN: Does art history exclude aesthetics?

JE: The answer depends on your examples and the purposes of your question and the public to which the question is aimed.

I can give you like a list of problems: the first problem is that aesthetics itself is a Western construct. Second, it has a specific history of motivations, from Baumgarten onward, emphatically including Kant, so it is open to—it demands—a historicized reading. But—a third problem—aesthetics considered as a philosophic discipline is non-historical or transhistorical, and in that sense its terms of understanding are inimical to historical understanding. A fourth issue is that aesthetics is universalizing in its claims and therefore constitutionally incapable of begining from the particular, except to take that particular as an instance of the universal. The book Art History versus Aesthetics turned on that particular issue. A fifth problem is that art historians as practitioners of the discipline of art history are trained not to articulate their own aesthetic preferences, which creates disparities in art historical texts, wherever aesthetic preferences can clearly be discerned in the texts, but can’t be given voice in the same text.

All five of these are problems that stand in the way of just saying, yes, art history is aesthetics. On the far side of these questions, you have some contemporary practices in Chinese writing in which the purpose of an art historical education is to be able to bring to the general public attention the aesthetic qualities that are inheritated in artworks regardless of their time and place.

LN: One of the projects you’re working on – another “never ending book” – focuses on “why art historians should learn to draw and paint”. I suspect that this demand has to do not only with the necessity for a true connection between theory and the creation process, but also with the necessity for a more creative art theory, something that makes sense especially if we think of the theoretical ‘panic’ we experiment after postmodernism. If I have understood correctly, you value the art writing of Jean-Louis Schefer as a good example of creative art theory. But what do you think about new terms like ‘altermodernity’ – recently coined by Nicolas Bourriaud? Is that an example of creative thought or just an ‘in progress’ reformulation of the old postmodernism?

JE: Let me take two parts of that question and divide them away and then answer the rest of the question.

LN: That seems to be my strategy for this interview, isn’t it?

JE: I think so, yes, one more time! (laughing) So, “altermodernity”, I think, makes no sense at all. I’ve read this text very carefully, I’ve taught it in a seminar. If you make a list of the metaphors Bourriaud uses to describe his concept you’re already in enormous trouble: he uses the metaphor of the “archipelago” and metaphors like the “rhizome”; there are many competing metaphors. “Altermodernity” also radically excludes the word “aesthetics”, I think because he got in so much trouble for his Relational Aesthetics book. I believe the word “aesthetics” only occurs once in the Tate Triennial book. Like many people, I would like to say that the Relational Aesthetics project is fundamentally an aesthetic project. So all I mean to say here is that I don’t think it’s a coherent position, so I can’t comment on it. I actually don’t think that it makes sense as a position, as an argument. It has enablening virtues, it enables practices, and people feel that they can use things that are in it, but as a critical position, I don’t see it.

The second thing I want to separate out in your question is the word “creativity”. Actually, I would myself try not to use it, because it is very hard to grasp exactly what is meant by “creativity”. I would rather use “practice,” because practice is a nice way of pointing to things that happened in space and time, with a real body in front of a real artwork. So the question, “Should art historians learn to draw and paint?” for me is a question of the relation between practice (standing, say, with a pencil in your hand and making marks on a blank sheet of paper over a period of days, weeks, months or years) and scholarship, reading and writing. And so the thing that many art historians miss when they have never actually drawn or painted anything is the plausible meanings that happen in the process of making artworks and the plausible degrees of articulation of insights and the paucity of articulable logical propositions in any sense and the plausible degrees of control over the artwork, exercised at any given time. I can almost always tell when an art historical text was written by an art historian who doesn’t draw or paint. One of the signs that an historical argument has been made by a non-artist, or non-practitioner (by which I mean, very simply, someone who has never picked up a charcoal or a brush) is the assumption that the tiniest mark was intentional and is therefore ready to be interpreted—as if the entire artwork were some semiotic system that’s waiting to be decoded. On the other hand, when some people write about art as artists, in a way that may not be useful to art historians because it is an attempt to replicate the non-conceptual continuum of experience that produced the object. Some of John Berger’s writing tries to be like this.

So, three things I’m excluding: the “altermodernity”, the creativity and Schefer. He doesn’t have to do with practice, but with trying to create a prose, a record in writing, in prose, which has the particularity and uniqueness of the art object and which replicates, in as much as writing ever can, the non-logical operations of an image. I think of him as constructing a response to the visual object that’s very much within language, even within semiotics, but not within logic.

I think the reason why I’ve never publish much of this material on the subject of why art historians should learn to draw and paint is that I still haven’t found a way to convince the art historians who have never drawn and painted that they actually should. I can make arguments, but I can’t make the kind of arguments that will make them turn off their computers and go and try to draw something.

LN: You have different books published in Korean or Czech, but not yet in Spanish. Knowing your reputation in Spain, I see this as a contradiction.

JE: It is nice of you to say that I have a reputation in Spain; it depends on who you ask. You know, the choice of what gets translated is always to some degree arbitrary. In my experience it depends on having one or two people in a country who happen to want to translate something and it’s only after the work is translated that the person has some visibility. As an extreme example of this is Tom Mitchell, very widely known in many different countries and widely known in German speaking countries. Germans, of course, are known for their virtuosity in English, so the assumption had been made that Mitchell was known there, just as any English speaking author could be, and that the students have no problem to reading him, but then few years ago some of his works were collected and translated, by Gustav Frank, and all of the sudden, he’s much more widely discussed in Germany. So even there, in a case where the language barriers are fairly minimal, Mitchell’s reputation is to some degree a consequence of a particular interest on Frank’s part.

There’s another issue to rise about translation into Spanish. At least after talking to Anna Maria Guasch and other Spanish people interested in visual studies and art history, it seems to me that the scholarly scene in Spain, in this subject at least, is extremely Anglophile. It would be very nice, I think, to change that orientation. There is a certain amount of French writing on art, as you know, in Spanish. There is almost no German or works in other languages; Scandinavian languages are almost completely absent. There are, as far as I know, two relatively important recent works in German art history in Spanish, one is a book of Hans Belting’s the other is a long essay by Oscar Bätschmann on hermeneutics. Other than that, I think there’s nothing.

There will be an anthology of my work in Spanish, but it would be best to have texts in other languages translated, because otherwise, you have the same situation as you were describing with Romania: a sudden jump into a discourse without continuity. And this brings us back to your own dissertation: your challenge is to leap over the lacuna in the reception of October in the Spanish speaking communities in such a way that you produce some sense of the organic necessity of these arguments that you’re interested in. If you don’t produce that sense of necessity, then you’re simply enacting another importation of theory which might or might not be read, at the discretion of each scholar. I agree with you that the October model, for better or worse, is an extremely important one, so the challenge is to make sure that it appears as necessary, when it appears in Spanish.

LN: We’ve started talking about the distance between art critics, art historians, artists. In relation to your own career, how do you negotiate between different publics?

JE: Because I do a lot of traveling when I’m lecturing, I’m very often in the position of trying to direct ideas to different publics. So yes, I'm actually very interested in reaching publics of different sorts. I don’t remember if I have mentioned to you, that I just started worked as a columnist for The Huffington Post. It’s probably not known in Spain, but it’s one of the largest politically left-leaning Internet news sites; it had 24 million unique visitors last year and one of the previous art writers in it wrote a column that got 3 thousand clicks per minute! So it’s a great job for me. I’ve just started it; my first column was Mondrian. It is an exemplary exercise for an academic: to try to speak in as many different ways as possible, to as many different publics as possible. Speaking to people who have read all the same books as you have, is easy by comparison.

Notas

[1] Loredana Niculet is working on a dissertation about the model of the avant-garde in Hal Foster, who's a member of the October editorial board.

[2] “Boutique Multiculturalism, or Why Liberals Are Incapable of Thinking about Hate Speech”. Stanley Fish, Critical Inquiry (1997), or www.jstor.org/stable/1343988 (with academic access).

[3] http://www.akad.se/Nussbaum.pdf.

[4] Vol. 4 of the Stone Art Theory Institute, co-edited with Harper Montgomery (University Park, PA: Penn State Press, 2012).

© Disturbis. Todos los derechos reservados. 2010